public

A Case Study in Motte-and-Bailey: “Be Reasonable” as a Shield for Extreme Health Claims

Introduction: The claim, the backlash, and the “reasonable” retreat

In September 2025, former U.S. President Donald Trump publicly connected prenatal acetaminophen (paracetamol/Tylenol) to autism and ADHD, punctuated by categorical admonitions such as “Don’t take Tylenol,” and amplified by a White House fact sheet asserting that use of acetaminophen in pregnancy—“especially late in pregnancy”—“may cause long-term neurological effects” in children. Those definitive lines ignited understandable pushback from clinicians and scientists.

What Trump actually said (Sept 22, 2025)

- “The meteoric rise in autism is among the most alarming public health developments in history.”

- “Tylenol during pregnancy … can be associated with a very increased risk of autism.”

- “So taking Tylenol is not good.”

- “We are … strongly recommending that women limit Tylenol use during pregnancy unless medically necessary.”

- “You have certain groups … the Amish … they have essentially no autism.”

- “Today, the FDA will issue a physician’s notice about the risk of acetaminophen during pregnancy and begin the process to initiate a safety label change.”

Sources: White House remarks transcript, Sept 22, 2025; administration fact sheet and agency materials.

The Facebook post we analyze opens with the claim that criticism of Trump is driven by “Orange Man Bad/TDS (Trump Derangement Syndrome)” bias: people reject what he says out of emotion, not reason (e.g., if Trump said the Sun is white, “they” would insist it is yellow). The author portrays Trump as erratic yet occasionally correct thanks to advisers, then revisits COVID-era ivermectin, arguing it was unfairly demonized despite being clinically safe and initially supported by small studies (while acknowledging larger trials later showed minimal benefit). Turning to Trump’s new assertion that acetaminophen (paracetamol/Tylenol) in pregnancy causes autism, the post concedes the evidence is “thin,” but highlights four studies reporting modest associations (1. a large Swedish cohort with sibling analyses, 2. an NIH cord-blood biomarker study, 3. a systematic review using the Navigation Guide, and 4. a multi-cohort European analysis). It repeatedly stresses “association ≠ causation,” notes that clinical guidance remains unchanged (use acetaminophen only when needed, low dose, short duration), warns that both hatred and idolization can cloud judgment, and ends with a call to read PubMed abstracts instead of Facebook comments. In tone and structure, it presents itself as a neutral, reasonable, data-driven plea for critical thinking.

This essay argues that the post is a textbook motte-and-bailey maneuver: the bailey (an expansive, indefensible claim) would be claiming that Trump’s categorical warning was substantively right or at least reasonable. When challenged, the defender retreats to the motte (a narrow, defensible truism): “some studies report an association; association ≠ causation; we should be calm and read the literature.” Once critics are exhausted disputing that narrow truism, the rhetoric flows back to the bailey—using the “be reasonable” stance as retroactive cover for the original, extreme claim.

What is the motte-and-bailey?

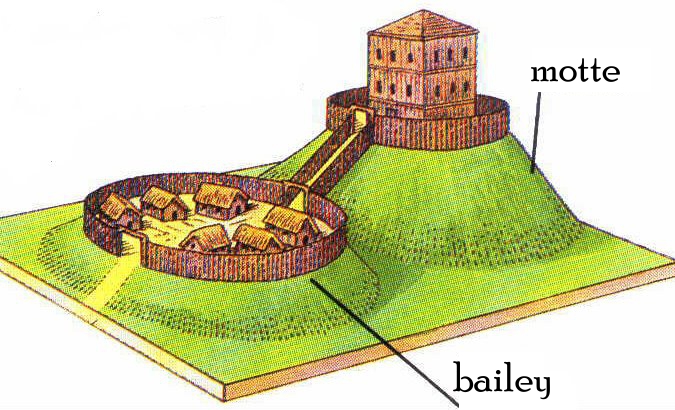

Coined by philosopher Nicholas Shackel, the motte-and-bailey fallacy is inspired by the design of medieval castles, and it describes a two-position strategy:

- Bailey: a broad, provocative claim that advances an agenda but is hard to defend.

- Motte: a modest, defensible claim that is easy to defend (often a near-tautology or widely accepted caveat).

When the bailey is attacked, its defender retreats to the motte. After critics are forced to concede the motte, the defender advances again as if the bailey had been vindicated.

Mapping the post onto the motte-and-bailey structure

The bailey (the extreme, categorical position)

- Trump’s categorical framing (e.g., “Don’t take Tylenol”) and official messaging that prenatal acetaminophen “may cause long-term neurological effects” function as sweeping, cause-implying guidance for the general public. Substantively, this is an alarmist leap beyond what current evidence can responsibly support.

The motte (the modest, defensible position)

The Facebook post switches to claims that are, in isolation, broadly defensible:

- Some studies report associations between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and later ASD/ADHD diagnoses.

- Association ≠ causation—confounding (e.g., genetics, indication such as maternal fever) can create spurious links.

- Guidance has not changed: clinicians still recommend acetaminophen in pregnancy—when needed, in the lowest effective dose for the shortest time.

Each of these is, on its own terms, accurate enough to withstand scrutiny. That is precisely why it works so well as a motte.

How the rhetorical sleight works

-

Equivocation between “there is a weak association” and “the President was right.” The post implicitly conflates two very different propositions: (a) a literature with mixed, mostly weak associations under significant confounding; versus (b) a categorical public directive. Defending (a) does nothing to justify (b). Yet by focusing readers on (a), the post encourages a mental shortcut that retroactively dignifies (b).

-

Framing dissent as irrational (“Orange Man Bad”). The post characterizes criticism of Trump as emotional or partisan, suggesting that people reject his claims because it’s Trump. This reframing subtly shifts the burden: instead of defending the categorical claim, the author attacks the critics’ motives. That move converts methodological objections into tribal overreaction—another classic motte tactic.

-

Selective calibration of uncertainty. On ivermectin, the post minimizes the weight of negative high-quality evidence and accentuates early, small, favorable studies; on acetaminophen, it highlights suggestive signals but downplays the sibling-control and confounding-by-indication findings. The consistent pattern is not “follow the evidence wherever it leads,” but “keep the door open for the preferred conclusion.” The motte here is “we should be cautious,” but the bailey it serves is “the controversial claim might be true—so stop criticizing it.”

-

False balance disguised as prudence. Presenting a split between “hysterical detractors” and “calm reason” implies equal evidentiary footing. But expert guidance rests on risk–benefit analysis and the quality hierarchy of evidence. Treating categorical public warnings and nuanced clinical guidance as two equally reasonable sides blurs that hierarchy—another way to drag the bailey under the motte’s umbrella.

-

Whataboutism as insulation. The ivermectin detour functions as reputational laundering: if “they were unfair about ivermectin,” perhaps they are unfair now. Even if that premise were true (it isn’t—large, rigorous trials did not show meaningful benefit), it is irrelevant to the acetaminophen question. The rhetorical utility is to pre-suspect critics and pre-excuse overreach.

Why the motte convinces—and why it misleads

- True-but-trivial cover: “Association ≠ causation” is undeniably correct. It’s also the default caveat in epidemiology. Repeating it loudly doesn’t transform speculative policy prescriptions into responsible public health advice.

- Reasonableness theater: Adopting the posture of “calm reader of abstracts” confers epistemic virtue while sidestepping the core problem: categorical messaging from a political podium can cause harm (e.g., untreated fever in pregnancy) even if a small association later proves real.

- Burden-shifting: Critics are dragged into debating the existence of any association, a far weaker claim than the original bailey. Once they concede the motte (“yes, some studies find weak signals”), defenders claim implicit victory for the bailey.

The eventual return to the bailey

After retreating to the motte—“We’re just saying there are studies; don’t be emotional; think critically”—the discourse predictably cycles back:

- Citation as absolution: The existence of a literature (no matter how tentative) is waved as a permission slip to keep repeating categorical warnings.

- Weaponized moderation: When clinicians push back (because categorical warnings conflict with standard-of-care risk management), they are labeled “ideological” or “anti-science,” recasting the original overreach as the truly “reasonable” stance.

- Policy by insinuation: The “just asking questions” posture nurtures a climate in which providers feel social pressure to deviate from guidelines, and patients avoid indicated treatment—outcomes aligned with the original bailey.

In short, the motte’s sober tone is later cited to defend the bailey’s sweeping, scientifically unsound claim—exactly the dynamic the motte-and-bailey concept was coined to describe.

What the evidence actually supports (and what it doesn’t)

- Signals exist: Multiple studies have reported weak associations between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and later ASD/ADHD diagnoses.

- Causation is unproven: Family-based designs (e.g., sibling comparisons) and confounding-by-indication (e.g., maternal fever) substantially dilute or explain observed associations.

- Clinical guidance remains unchanged: For fever and significant pain in pregnancy, acetaminophen is still the recommended first-line option, used judiciously (lowest effective dose, shortest duration). NSAIDs, by contrast, carry known late-pregnancy risks.

- Public health messaging must weigh harms: Categorical “don’t take Tylenol” guidance ignores the risks of untreated fever/pain and substitutes political certainty for scientific uncertainty.

How to spot motte-and-bailey in health debates

- Identify the bailey: What is the sweeping, provocative claim? Would following it change behavior in ways guidelines do not endorse?

- Find the motte: What narrow truism is offered when the bailey is challenged (e.g., “some studies suggest,” “let’s be cautious,” “association ≠ causation”)?

- Watch for the shuttle: Does the defender oscillate—retreating to the truism under scrutiny, then later reasserting the sweeping claim as if validated?

- Check alignment with expert risk–benefit guidance: Are clinical trade-offs acknowledged, or are they waved away by ideological framing?

- Beware reputational decoys: Appeals to prior controversies (e.g., ivermectin) are often noise designed to preemptively discredit criticism in the present case.

Conclusion: Don’t confuse a caveat with a warrant

A call to “be reasonable” is admirable when it clarifies trade-offs and reduces harm. It becomes a motte-and-bailey when it is used to launder an indefensible, categorical claim through a haze of modest truisms. In the Tylenol–autism episode, the public was offered a stark directive that outran the evidence and clashed with established obstetric care. The Facebook post’s “calm” retreat to weak associations and generic caveats does not repair that harm; it camouflages it.

The antidote is simple, if not easy: keep the bailey and the motte separate in your mind. Demand that categorical claims meet categorical standards of evidence, and refuse to let reasonable caveats be conscripted to defend unreasonable edicts.